top of page

Meet the salamanders:

The "Tiny" Mural at GSU celebrates the salamanders of Georgia, which vies with North Carolina for the greatest number of species in North America. To learn more about these species, check the gallery below.

Collaborators: Dr. Harvey, Biology Professor,

Art Professor DesChene,

+ Art Professor Schmuki.

Big thanks for the grant from GSU and the

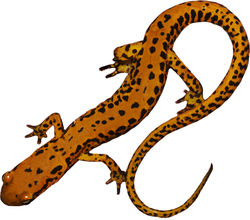

Spotted Tail SalamanderEurycea lucifuga Photo courtesy of Ben Lowe As their name implies, cave salamanders are normally found in or near caves or similar rocky habitats, which they expertly navigate using their prehensile tail. |  Dwarf SalamanderEurycea quadridigitata Photo courtesy of Pierson Hill Unlike most southeastern salamanders, this species has only four toes on its hind feet. It remains motionless when disturbed, probably to avoid detection by potential predators. Probably the commonest salamander on campus. |  Dwarf SalamanderEurycea quadridigitata Photo courtesy of Adam Cooner Unlike most southeastern salamanders, this species has only four toes on its hind feet. It remains motionless when disturbed, probably to avoid detection by potential predators. This is probably the commonest salamander on campus. |

|---|---|---|

Eastern HellbenderCryptobranchus alleganiensis Photo courtesy of Nathanael Herrera The hellbender is an aquatic salamander that just barely reaches the northern portions of Georgia. The flattened, wrinkled body is distinctive, as is its very large size. Like amphiumas (the other large aquatic salamanders in our area), hellbenders are very slippery and capable of delivering a painful bite, but unlike the amphiumas, their numbers are in rapid decline thanks to habitat loss and degradation. |  Eastern Hellbender(Larvae) Cryptobranchus alleganiensis Photo courtesy of Jake Scott The hellbender is an aquatic salamander that just barely reaches the northern portions of Georgia. The flattened, wrinkled body is distinctive, as is its very large size. Like amphiumas (the other large aquatic salamanders in our area), hellbenders are very slippery and capable of delivering a painful bite, but unlike the amphiumas, their numbers are in rapid decline thanks to habitat loss and degradation. |  Eastern NewtNotophthalmus viridescens Photo courtesy of Brian Grathwicke Eastern newts have an unusual life history: the aquatic larvae emerge as terrestrial juveniles called efts, which can take up to seven years before completing their metamorphosis to the primarily aquatic adult form. All stages are toxic, especially the brightly colored efts. |

Eastern NewtEaster Newt Notophthalmus (Eft Stage) Notophthalmus viridescens Photo courtesy of Dave Burkart Eastern newts have an unusual life history: the aquatic larvae emerge as terrestrial juveniles called efts, which can take up to seven years before completing their metamorphosis to the primarily aquatic adult form. All stages are toxic, especially the brightly colored efts. |  Frosted Flatwoods SalamanderAmbystoma cingulatum Photo courtesy of Jake Scott Historically found in the Coastal Plain of Georgia, Florida, and South Carolina, this species is now listed as federally threatened due primarily to habitat loss. |  Greater Siren LarvaeSiren lacertina Photo courtesy of Jake Scott Sirens are large, aquatic salamanders with external gills and only a pair of front legs. Both greater and lesser sirens are found in campus waters; they are difficult to distinguish without careful inspection. |

Georgia Blind SalamanderEurycea wallacei Photo courtesy of Daniel Thompson Like many troglobitic (cave-dwelling) species, Georgia Blind Salamanders have a host of unusual features. Although sensitive to light, their eyes are mere dark spots covered by skin; they retain larval characters as adults (although the larvae have never been seen); their skin almost completely lacks pigmentation. |  Green SalamanderAneides aeneus Photo courtesy of Justin Oguni Although the Green Salamander is restricted to moist crevices in rock formations, scientists think it was originally an arboreal species that lived under the bark of tall hardwood trees until widespread deforestation by humans forced it to adapt to its current habitat. |  Long-tailed SalamanderEurycea longicauda Photo courtesy of Bonnie Ott Although widespread, often abundant, and attractive, this species has been poorly studied, and little is known about its behavior, reproductive biology, lifespan, or interactions with other species. |

Lesser SirenSiren intermedia Photo courtesy of Pierson Hill Sirens are large, aquatic salamanders with external gills and only a pair of front legs. Both greater and lesser sirens are found in campus waters; they are difficult to distinguish without careful inspection. |  Marbled SalamanderAmbystoma opacum Photo courtesy of Patrick Coin Much like fingerprints in humans, the highly variable black-and-white patterning can be used to identify Individual marbled salamanders. Unusual for mole salamanders, females lay their eggs on land and guard them until winter rains flood the nesting site. |  Marbled SalamanderAmbystoma opacum Photo courtesy of Patrick Coin Much like fingerprints in humans, the highly variable black-and-white patterning can be used to identify Individual marbled salamanders. Unusual for mole salamanders, females lay their eggs on land and guard them until winter rains flood the nesting site. |

Marbled SalamanderAmbystoma opacum Photo Jim Petranka Much like fingerprints in humans, the highly variable black-and-white patterning can be used to identify Individual marbled salamanders. Unusual for mole salamanders, females lay their eggs on land and guard them until winter rains flood the nesting site. |  Marbled SalamanderAmbystoma opacum Photo courtesy of Steven David Johnson Much like fingerprints in humans, the highly variable black-and-white patterning can be used to identify Individual marbled salamanders. Unusual for mole salamanders, females lay their eggs on land and guard them until winter rains flood the nesting site. |  Mole SalamanderAmbystoma talpoideum Photo courtesy of Todd Pierson Some mole salamanders retain their aquatic larval characteristics as adults, a phenomenon known as neoteny. If their pond dries up, however, they can complete their metamorphosis and move into the adjacent forest. |

Ocmulgee Slimy SalamanderPlethodon ocmulgee Photo courtesy of Alan Cressler Molecular data published in 1989 separated the single Northern Slimy Salamander into at least 13 different species, including the Ocmulgee Slimy Salamander, which is found on campus. Slimy salamanders get their name from the copious amounts of toxic, sticky mucus they secrete when disturbed. |  Patch-nosed SalamanderUrspelerpes brucei Photo courtesy of Kevin Stohlgren The Patch-nosed Salamander is noteworthy for several reasons. It is the smallest species of salamander in North America. It is the only North American salamander in which males and females have completely different coloration. Described in 2009, it was the first new North American genus to be described since 1961. |  Patched Nose SalamanderUrspelerpes brucei Photo courtesy Todd Pierson The Patch-nosed Salamander has several distinctions (wording?). It is the smallest species of salamander in North America. It is the only North American salamander in which males and females have completely different coloration. Described in 2009, its was the first new North American genus to be described since 1961. |

Pigeon Mountain SalamanderPlethodon petraeus Photo courtesy of Richard Williams The Pigeon Mountain Salamander has the most limited distribution of any Georgia salamander, restricted to limestone outcrops and adjacent woodlands on the eastern side of Pigeon Mountain in northwestern Georgia. |  Red-legged SalamanderPlethodon shermani Photo courtesy of John Williams The geographic range of this species is limited to parts of the Nantahala and Unicoi Mountains, but fortunately much of this area is protected national forest. |  Red SalamanderPseudotriton ruber Photo courtesy of Mike Graziano Although this salamander secretes mild toxins, its striking colors may provide greater protection by mimicking more dangerously poisonous salamanders, such as red efts. |

Spring SalamanderGyrinophilus porphyriticus Photo courtesy of Todd Pierson This large, colorful salamander is a major predator of smaller salamanders, including members of its own species. Adults forage both in water and on land. |  Spotted Salamander(Larvae) Ambystoma maculatum Photo courtesy of Jonathan Mays The eggs of spotted salamanders may be clear or opaque, depending on a single genetic mutation. Additionally, many egg masses appear green due to a poorly understood symbiotic relationship with green algae. This species is less common in the Coastal Plain than elsewhere in the state. |  Spotted SalamanderAmbystoma maculatum Photo courtesy of Brian Grathwicke The eggs of spotted salamanders may be clear or opaque, depending on a single genetic mutation. Additionally, many egg masses appear green due to a poorly understood symbiotic relationship with green algae. This species is less common in the Coastal Plain than elsewhere in the state. |

Two-toed AmphiumaAmphiuma means Photo courtesy of Brian Gratwicke. At up to 45 inches in length, two-toed amphiumas are our largest salamanders. These strange, fully aquatic salamanders lack external gills, and their eyes and legs are greatly reduced, with each leg possessing only two tiny toes. |  Southern Two-lined SalamanderEurycea cirrigera Photo courtesy of Jake Scott This common species can be found under fallen logs on campus, often far from standing water. |  Lesser Siren(Larvae) Siren intermedia Photo courtesy of Pierson Hill Sirens are large, aquatic salamanders with external gills and only a pair of front legs. Both greater and lesser sirens are found in campus waters; they are difficult to distinguish without careful inspection. |

bottom of page